The television programme Say Yes To The Dress has had a lot of success since it first aired in 2007. Although pop culture influences are often dismissed “in contrast to the ‘hard’ powers of the legal system and the economy” (Mendick, Allen & Harvey, 2015, p. 167) the ideological messages the show carries have the potential to encourage marriages and highly commercialized weddings among viewers. These romantic, and yet, consumerist ideals surround women everyday meaning many have internalized ideas about the importance of love, the exceptionalness of a certain wedding dress and the need to spend excessive amounts of money to mark any rite of passage. These beliefs then reinforce systems of power, such as patriarchy and neoliberalism.

The fatalism of relationships is highly romanticized within our culture, but on Say Yes To The Dress the perfect wedding dress is referred to as ‘the one’ more than the bride’s finance is referred to as ‘the one’. Brides frequently dismiss a dress because, although they think it is pretty, they did not get a certain feeling. They believe that the perfect dress will be magically revealed to them (Otnes & Lowrey, 1993, p. 326); in the same way we are trained to believe that if we find the right partner we will just know. “Emotional involvement is high when it comes to purchasing” the wedding dress (Singh Mann & Sahni, 2015, pp. 179-180) as it is often considered a “sacred artifact” (Otnes & Lowrey, 1993, p. 326) and is seen as the material embodiment of romantic sentiment (Boden, 2003, pp. 103-104). This is evident in the very title of the show, as women are encouraged to say ‘yes’ to the dress, in the same way they said ‘yes’ to their fiancés proposal of marriage (see fig.04). In this way, “consumption can become a vehicle of transcendent experience” ((Belk, Wallendorf & Sherry, 1989, p. 11).

Consultants on the show will often try to convince women to spend over their budget and remind them that it is ‘their special day’ and their ‘one chance’. The consequences of spending more money than the bride is able to pay is not discussed and the money is seen as a willing sacrifice in order to construct each bride’s own perfect wedding day (Boden, 2003, p. 157). After all, brides grow up “with a particular fantasy image of their wedding day” (Otnes & Lowrey, 1993, p. 326) and will not have the opportunity to repeat the occasion unless their marriage fails (Boden, 2003, p. 72).

Only the bride, and not the groom, is conditioned into feeling that certain wedding items are sacred, and wedding consumption “promotes stereotypical forms of gendered behaviour” (Boden, 2003, p. 154). In fact, in modern Western culture, all consumption is “a thoroughly ‘gendered’ activity” (Campbell, 1997, p. 167). This is evident in the bridal parties featured on Say Yes To The Dress, the majority of friends and family members brought along by brides are female (see fig.05). Campbell suggests that women are more skilled than men at shopping because females are “socialized into being the aesthetically skilled gender” (1997, p. 171).

Perhaps this is why weddings typically focus much more on the bride than they do the groom. On Say Yes To The Dress, the bride’s fiancé is only ever briefly mentioned when the bride says a little bit about herself (see fig.02). Throughout all media surrounding weddings, there is rarely any discussion of life after the wedding for the couple. It is as if the marriage does not matter, only the wedding event is significant.

The wedding industry revolves around the bride’s identity. Thanks to wedding fayres and sites like Pinterest, which is full of wedding inspiration ideas, brides can personalize their weddings to their specific tastes and have endless choices of not only dresses but also chairs, flowers, venues and so on. Brides are told to “communicate themselves through their purchases” (Singh Mann & Sahni, 2015, p. 180) and though choice is enormously emphasized, this is perhaps a false freedom of choice (Lee, 2008, p. 2). The choice is only between things to consume, “rather than their choice of whether or not to consume” (Boden, 2003, p. 145). Hence, the agency of brides is often illusory (Boden, 2003, p. 158) despite the fact they are constantly reminded that this is their wedding.

At her own wedding is also one of the few times a woman is allowed to be openly narcissistic. Women at trained to believe that their appearance is of the utmost importance and therefore brides are “subject to a series of internal and external surveillance mechanisms” (Boden, 2003, p. 66). The focus on the bride’s looks can often lead to objectification of the bride, by herself and others. She becomes “the ‘beautiful bride’ in the spotlight rather than the individual human being about to consummate an important relationship” (Lewis, 1997, p. 183).

Frequently, Brides long to look like a princess, meaning discourse around weddings almost always involves some discussion of ‘fairytale’. This conjures up an image of youthful beauty. But it could be said that the ideologies of a ‘fairytale’ romance disempowers women, as fairytales almost always involve the female protagonist either getting rescued by a man, or becoming her ‘true self’ once she meets the perfect man.

Due to the traditional structure of our society, many women “define themselves as successful according to their ability to sustain sexually loving relationships” (Wolf, 1990, p. 145), meaning weddings become the true symbol of accomplishment. This can easily leads to the assumption that women “require love and marriage” (Boden, 2003, p. 119) and cannot be considered “‘real women’ unless they marry and bear children” (Haskell, 1987, p. 2).

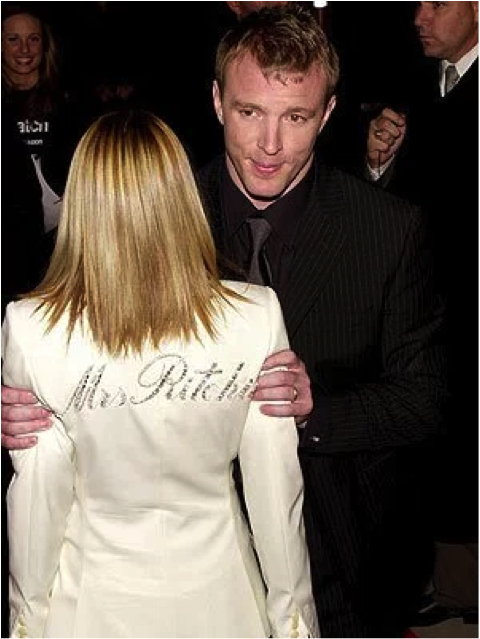

In spite of this, many believe that the institution of marriage itself exploits women and naturalizes unequal power relations. Traditional marriages sanctioned “a woman’s property (and the woman herself as property) be passed into the hands of the man she was to marry” (Boden, 2003, p. 15) and until 1992 rape within marriage was still legal in the United Kingdom (The Law Commission, 1992). Even now, powerful women, such as celebrities like Madonna, have posed in clothing decorated with diamantes spelling out their husband’s name, as if, now they are married she is his property (see fig.03).

Moreover, the “allocation of the housewife role to the women in marriage is socially structured” (Oakley, 1987, p. 2) and this role has “more or less clear patterns of expectations attached” to it (Wells, 1970, p. 168), meaning wives do all or nearly all of the domestic work even though many women now also do full-time paid work (Wolf, 1990, p. 23).

Because of the belief that marriage serves society, until recently, the government provided tax breaks for married couples. Now, however, “television is being reinvented as an instructional template for taking care of oneself” (Skeggs & Wood, 2012, p. 29), hence, some might believe that programmes like Say Yes To The Dress are teaching girls that marriage and a costly is a normal direction in a stable life. This will perhaps mean there are less women are children becoming a burden on the state, “enabling the state to decrease its social responsibilities” (Skeggs & Wood, 2012, p. 29) and more money being spent by couples. Lewis points put that ultimately, this system of self-betterment “serves to preserve class divisions and keep capital in the hands of a few” because “In striving to be like elites, middle-class consumers hand over capital – and thus power – to the elites” (Lewis, 1997, p. 186).

Even though same-sex marriage is now legal in the United Kingdom, wedding centred media, like Say Yes To The Dress, continues to, what Boden refers to as, ‘romance’ heterosexual love by rarely showing anything but husband and wife couples (2003, p. 52). On the exceptional occasion when the show has shown a lesbian pairing, this is presented to us as an anomaly.

Because marriage has lost much of its religious significance for many people, the wedding industry has redefined weddings as a commercialised event, rather than a symbolic occasion. This means that weddings are now judged by their monetary value and couples use the event to “enhance their social acceptability” by flaunting their wealth in front of friends and relatives (Singh Mann & Sahni, 2015, pp. 179-180). Competition often arises between brides and friends, or even mothers-of-the-bride with their friends.

In our culture of excess, “consumption and satisfaction are equated” (Lewis, 1997, p. 174), thus “consumerism is legitimated and promoted through such ritualized activities as expensive formal weddings” (Lewis, 1997, p. 186). In Say Yes To The Dress, for example, when displaying information about the bride her budget is at the top while her wedding date and fiancé’s name are lower down, suggesting that the money she is willing to spend is the most important aspect of her wedding (see fig.02). This consumer ideology supports a “way of experiencing social reality that is compatible with the needs of a mass-production, mass-consumption, capitalist society” (Parenti, 1993, p. 71). Because consumerism plays on real human needs in a deceptive way (Parenti, 1993, p. 72), it is now common practice for many rite of passages and milestones to be marked with flaunting of wealth, and this is encouraged in many aspects of the media, for example, the television show My Super Sweet Sixteen.

Thanks to neoliberalism, which is “operating as a form of ‘common sense’” in our society and in turn legitimating the market (Couldry, 2008, p. 4), spending is promoted and people are trained to believe that anyone can have their dream wedding as long as you work hard and focus on yourself, despite any disadvantages you might have. This ideal is shown to us on Say Yes To The Dress through these normal women, who are able to buy their perfect (and expensive) dress because they followed the rules of capitalism. The programme indirectly heartens viewers that they can have that, too.

Say Yes To The Dress and other wedding focused media has triumphed, marked by the Say Yes To The Dress spinoffs (see fig.01), along with the vast choice of wedding television programmes such as Don’t Tell The Bride and Four Weddings. These, as well as the excitement of the Royal Wedding and other celebrity weddings, suggest a public fascination with the wedding industry and “may serve to increase the endorsement” of them (Hefner, 2016, p. 320). The focus on consumerism could persuade viewers to spend excessive amounts of money, that they perhaps do not have. This individualistic nature could also make viewers unable to afford such weddings feel guilty for not working hard enough and being, in capitalisms eyes, a failure. In addition to this, the romantic ideology and self-surveillance that Say Yes To The Dress upholds may possibly keep women vulnerable within our patriarchal society.

Appendix

Fig.01 – List of Say Yes To The Dress Spinoffs

This list of Say Yes To The Dress spinoffs demonstrates the success of the series. With eight spinoffs of the show and many other wedding reality television programmes currently on television, it is clear that the public enjoy watching shows that revolve around weddings. (“Say Yes To The Dress,” n.d.)

This list of Say Yes To The Dress spinoffs demonstrates the success of the series. With eight spinoffs of the show and many other wedding reality television programmes currently on television, it is clear that the public enjoy watching shows that revolve around weddings. (“Say Yes To The Dress,” n.d.)

Fig.02 – Bride Information, Say Yes To The Dress Screencap

This image, taken from Say Yes To The Dress, shows the standard layout that all episodes of Say Yes To The Dress use to display to audiences the information about the brides appearing in that episode. The layout of the information could to us something about the priorities of the wedding industry. First, the information is about the bride specifically, telling audiences that it is the bride who is most important. It suggests that it is the bride’s day and reinforces theories about the wedding revolving around the bride’s identity. Just below her name is her budget for her dress, implying that the amount she can spend on the dress is essential because, after all, according to the wedding industry the more money spent the better the wedding will be. At the bottom of the list of information is the name of the bride’s fiancé, perhaps telling audiences that as long as you are getting married, it is does not matter so much who you are marrying. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

This image, taken from Say Yes To The Dress, shows the standard layout that all episodes of Say Yes To The Dress use to display to audiences the information about the brides appearing in that episode. The layout of the information could to us something about the priorities of the wedding industry. First, the information is about the bride specifically, telling audiences that it is the bride who is most important. It suggests that it is the bride’s day and reinforces theories about the wedding revolving around the bride’s identity. Just below her name is her budget for her dress, implying that the amount she can spend on the dress is essential because, after all, according to the wedding industry the more money spent the better the wedding will be. At the bottom of the list of information is the name of the bride’s fiancé, perhaps telling audiences that as long as you are getting married, it is does not matter so much who you are marrying. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

Fig.03 – Photograph of Madonna’s ‘Mrs Richie’ Jacket

This photograph from January 2001 shows Guy Richie holding his new wife, Madonna, in place to display her jacket, which is encrusted with diamantes that read, “Mrs Richie”. Following this jacket, a trend began among celebrities and regular women to wear personalised items of clothing, particularly bikinis, with your new husbands name on. This craze echoes the disturbing history of the institution of marriage, in which women were considered their husbands property. In this image in particular, this notion is furthered by the fact that Guy Richie is holding Madonna by the shoulders with both hands holding her in place for everyone to see. In addition, the items of clothing are almost always white, continuing the bridal identity and continuing the tradition of the bride wearing white to symbolise her purity. Exceptionally worrying is the fact that the celebrities taking part in this trend are strong independent women, perhaps suggesting that even autonomous women succumb to the romanticised ideal of marriage and the institutionalised dominance of the husband. (People Style, 2008).

Fig.04 – Title, Say Yes To The Dress Screencap

The title of Say Yes To The Dress is reminiscent of the answer to a wedding proposal. The comparison inferred between a bride’s fiancé and her dress, suggests that the wedding dress is as important as the husband. This focus links to Belk, Wallendorf and Sherry’s theory of sacred consumption. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

The title of Say Yes To The Dress is reminiscent of the answer to a wedding proposal. The comparison inferred between a bride’s fiancé and her dress, suggests that the wedding dress is as important as the husband. This focus links to Belk, Wallendorf and Sherry’s theory of sacred consumption. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

Fig.05 – Bridal party, Say Yes To The Dress Screencap

This image shows one woman’s bridal party, consisting of her female friends and the female members of her family. The fact that she has only chosen to bring women, or only women wanted to come, demonstrates how shopping, particularly wedding shopping, is viewed as a woman’s activity. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

This image shows one woman’s bridal party, consisting of her female friends and the female members of her family. The fact that she has only chosen to bring women, or only women wanted to come, demonstrates how shopping, particularly wedding shopping, is viewed as a woman’s activity. (Broomhead & Winston, 2009).

Bibliography

- Belk, R., Wallendorf, M., & Sherry, J. F. (1989). The Sacred and the Profane in Consumer Behaviour: Theodicy on the Odyssey. Journal of Consumer Research, 16, 1-38.

- Boden, S. (2003). Consumerism, Romance and the Wedding Experience. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Broomhead, E., & Winston, J. (Directors). (2009). Once Upon A Dresss [Television series episode]. In N. Sorrenti (producer), Say Yes To The Dress. USA: Half Yard Productions.

- Campbell, C. (1997). Shopping, Pleasure and the Sex War. In P. Falk, & C. Campbell (Eds.), The Shopping Experience (pp. 166-176). London: Sage.

- Couldry, N. (2008). Reality TV, or The Secret Theater of Neoliberalism. Review Of Education, Pedagogy & Cultural Studies, 30(1), 3-13.

- Haskell, M. (1987). From Reverence to Rape (2nd ed.). London: University of Chicago Press.

- Hefner, V. (2016). Tuning Into Fantasy: Motivations to View Wedding Television and Associated Romantic Beliefs, Psychology Of Popular Media Culture, 5(4), 307-323.

- Lee, H. J. (2008, May). No Adults Left Behind: Reality TV Shows as Educational Tools in the Neoliberal Society. Paper presented at the meeting of the International Communication Association.

- Lewis, C. (1997). Hegemony in the ideal: Wedding photography, consumerism, and patriarchy. Women’s Studies In Communication, 20(2), 167-188.

- Mendick, H., Allen, K., & Harvey, L. (2015) ‘We can Get Everything We Want if We Try Hard’: Young People, Celebrity, Hard Work. British Journal of Educational Studies, 63(2), 161-178.

- Oakley, A. (1987). Housewife: High Value-Low Cost. London: Penguin.

- Otnes, C., & Lowrey, T. (1993). ‘Til Debt Do Us Part: The Selection and Meaning of Artifacts in the American Wedding, Advances in Consumer Research, 20(1), 325-329.

- Parenti, M. (1993). Inventing reality: the politics of the news media (2nd ed.). New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- People Style. (2008, August 11). Madonna: 50 Looks We Can’t Forget. People. Retrieved from http://www.people.com/

- Say Yes To The Dress. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.en.wikipedia.org/

- Singh Mann, B. J., & Sahni, S. K. (2015). Exploring the drivers of status consumption for the wedding occasion. International Journal Of Market Research, 57(2), 179-202.

- Skeggs, B., & Wood, H. (2012). Reacting to Reality Television: Performance, Audience and Value. London: Routledge.

- The Law Commission. (1992). Criminal Law: Rape Within Marriage (HC 167). London: HMSO.

- Wells, A. (1970). Social Institutions. London: Heinemann

- Wolf, N. (1990). The Beauty Myth. London: Vintage.